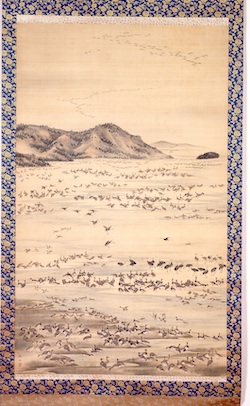

vol.21 In Between Realism and Fantasy: Wild Geese

Geese are part of the waterfowl species, like ducks and swans. Typically, waterfowl have round and inflated bodies, flat beaks, webbed feet and share similar body shapes- thus, they are mainly differentiated through their size. Generally, ducks represent the smaller species, geese the medium-sized species, and swans would be the big white species (, the only big black species being black swans). Ornithologically speaking, this classification is correct. Amongst the waterfowl, geese are neither as diverse as ducks, nor as graceful and friendly as swans, but, due to their unapproachable wildness and nobility, they are extremely popular with bird experts.

Geese of the northern hemisphere breed mainly in the vast wetlands of Siberia and winter in the temperate regions of Europe, America, and East Asia. Around 10 species migrate to Japan, and the Greater White-Fronted Geese (body length 72 cm) and Bean Geese (85 cm) migrate in large numbers and, thus, are seen relatively often. That said, the number of destinations they winter to are rather limited. They used to be seen all over Japan but, after world war II, there was a sharp decline and now they spend their winters around Hokkaido, Tohoku and the regions around the Sea of Japan, namely Niigata to Shimane (very few geese fly to other regions). They begin to arrive around the end of September, huddle and sleep in large herds at the large lakes and marshes and, during the day, eat gleanings and grass roots from paddy fields. By February, they gradually begin to head north and by May they leave for Siberia to breed.

This work captures to moment when five Greater White-Fronted Geese are about to descend on undulating water. A goose in the foreground flaps its wings just before landing, while the remaining four follow behind, shadowing its descent. The Greater White-Fronted Geese often live in families, so these five geese may be a family, with two being the parents and, the remaining three, their young. It would be highly unlikely that they would fly so close together when landing, as such, their arrangement in this picture is unrealistic. However, the way their descent is painted, as if they were falling from the sky, is indeed dramatic.

Let us take a closer look at the way these Greater White-Fronted Geese are depicted. The shape and balance of all their body parts is depicted accurately. Their neck and wings are neither too long nor too short, their body is firm, and their tails are thick and short. Above all, their wing feathers are depicted brilliantly. Like the real thing, the large outer flight feathers of the primary and secondary wings are painted black. With much care and precision, each feather is painted with one stroke in differing shapes and lengths, and the number of feathers is roughly correct. Above those feathers, you can see the arrangement of greater coverts and primary coverts, which are painted a deep blackish brown with visible white spots on the outer edge. Further above, the alula feathers and median coverts are depicted also with small white spots on their outer edges. On top, is a row of lesser coverts that is painted a light blackish brown. These variations and color gradations are as detailed as natural history illustrations and handbooks of birds. Furthermore, the pale orange beak and white band on their base, a key feature of the Greater White-Fronted Geese, is well captured, reflecting Seitei’s high skills of observation and painterly realism.

Nevertheless, there are several mistakes. The Greater White-Fronted Geese’s tail has a white band on its outer edge, however, in this work, it is painted blackish brown. Neither are the parts between the tail and waist, nor the rachis of the primary and secondary flight feathers, painted white. Furthermore, their faces are far too elongated. Even more, these Greater White-Fronted Geese lack the black spots that should be on their chest to their abdomen. Black spots are the only decorative aspect of the adult species, and there would be no aesthetic reason to omit them. Perhaps Seitei only modelled young geese.

Next, let us look at the birds in relation to the background. These geese are landing on raging waves. Realistically speaking, this scene would not occur in nature and is ornithologically incorrect. In fact, while Greater White-Fronted Geese can swim well, they live in the calm waters of lakes and rivers. Some waterbirds, like ducks, cormorants, and gulls, live in the rough sea, however, the Greater White-Fronted Geese are rarely seen in such settings. As such, the many Japanese paintings that depict these geese, i.e. Ito Jakuchu’s “Wild Goose and Reeds” (The Imperial Household Agency’s Museum of Imperial Collections) and Mori Tetsuzan’s “Geese” (Kumamoto Prefectural Museum of Art), present them in calm watersides.

Mori Tetsuzan “Geese”

Kumamoto Prefectural Museum of Art

I suspect Seitei knew the biology of the Greater White-Fronted Geese, and intentionally overlooked it. By placing the geese together with the waves, he was able to realize his artistic goal. While this scene was a fantasy, the realism of his work has the power to prevent viewers from ever noticing it.

Author : Masao Takahashi Ph.D. (Ornithologist)

Dr. Masao Takahashi was born 1982 in Hachinohe (Aomori prefecture) and graduated from Rikkyo University’s Graduate School of Science. Dr. Takahashi specializes in behavioral ecology and the conservation of birds that inhabit farmlands and wet grasslands. Focusing on the relation between birds and art, he has participated in various museum and gallery talks.