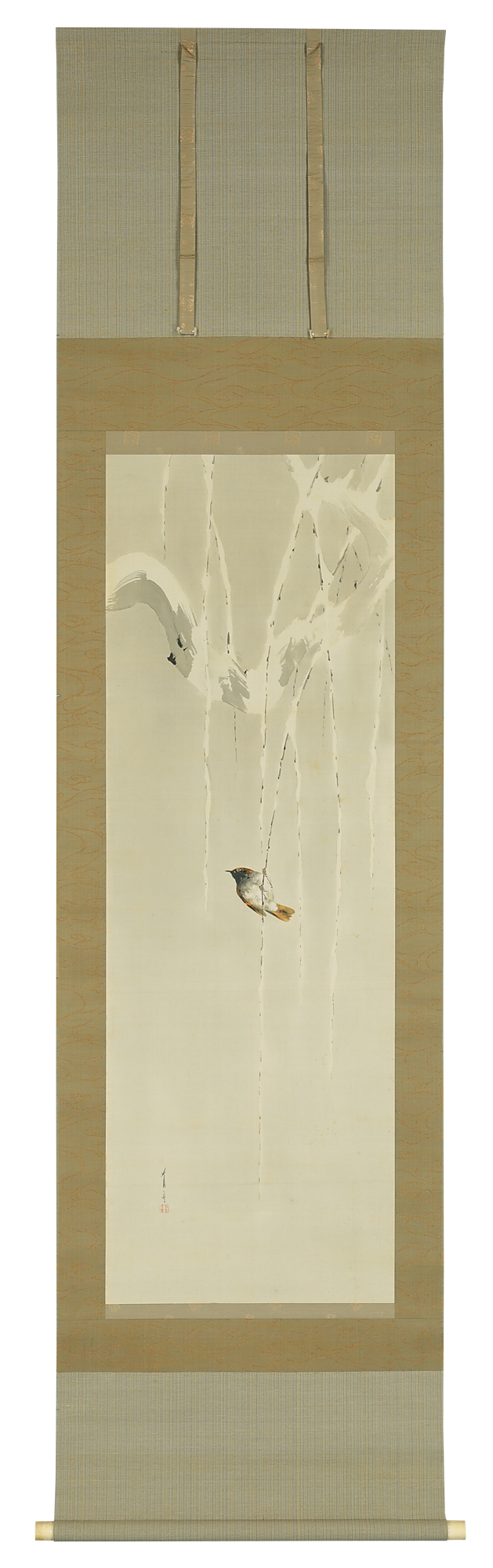

Color on silk, with a box signed and sealed by the artist,

artist's seal woven into the mount

vol.24 The Nihonga Painter who Loves Birds the Most: Willows in Snow

Which Nihonga (Japanese style) painter is the best at painting birds? I previously addressed this question in a talk show however, since I was unaware of Seitei at the time, he was not mentioned. The talk show participants offered various suggestions, from Ito Jakuchu to Maruyama Okyo, Okamoto Shuki, Katsushika Hokusai, Takeuchi Seiho and, the living artist, Uemura Atsushi. Although many proposals included the names of these great artists, none were in my personal ranking, which was shaped by my own tastes and preferences.

In first place was Miyamoto Musashi (Niten), also known as “Kensei” (lit: sword saint). Even to this day, I consider his work, “Shrike in Barren Tree” (Kuboso Memorial Museum of Arts, Izumi), the best bird-and-flower painting in the history of Japanese painting. Perhaps it was only him, a master swordsman, who could rightly capture the “predatory ambiance” of the shrike. For second place, I proposed Tanaka Isson (I will explain this reason later), and, for third place, Hayami Gyoshu. However, in reconsideration, Watanabe Seitei seems likely to win third place.

What if, instead, we asked “who was the nihonga painter who loved birds the most?” Of course, I, too, am a bird-lover and can tell if one is like-minded, just by sense alone. For painters, you could tell if they had an affinity for birds by the kinds of birds they would depict. For instance, great bird-lovers would add subtle nuances only experts would notice. These painters evidence their want to be valued by bird-lovers, by depicting birds that are uncommon but are not extremely rare. In depicting a great variety of birds, from Water Rails to Long-eared Owls, White-throated Needletails and Daurian Redstarts, I am certain that Seitei was a great bird-lover. Nevertheless, considering Tanaka Isson’s unmatched lineup of birds, I can say with confidence that he is arguably the ultimate bird-lover in the history of Japanese painting.

Let’s discuss the birds Isson has depicted. His works, as well as the birds he depicts, varies largely according to those made before and after his move to Amami Oshima Island. In his early career, he would often depict birds that regularly habituate the Satoyama (the woodlands near populated areas) of the Kanto region, such as the Azure-winged Magpie, the Eurasian Jay, the Scaly Thrush and the Eurasian Wren. Along these, a masterpiece to note “White Flower” (Tanaka Isson Memorial Museum), depicts a resting Scaly Thrush. In his later works, he mainly depicts the birds that live in Amami Oshima. In this period, he depicts many island-based species that are popular with bird-lovers, such as the Lidth’s Jay, the Owston’s Woodpecker and the Ruddy Kingfisher. Within the dense and distinct botanic landscape of the subtropics, the birds of his paintings have a realism and vitality that borderlines lifelikeness. As such, in this ranking of “Nihonga painters who are best at painting birds,” he deserves to be placed second.

One particular bird in Amami Oshima that Isson loved to paint was a small bird called the Ryukyu Robin. The Ryukyu Robin is endemic to Japan and solely inhabits the Ryukyu islands. They are characterized by their red-brown back, white belly and, for males, a black face. It was depicted occasionally in Edo period bird-and-flower paintings, so its existence seems to have been common knowledge for a long period. (They may have been distributed as domesticated birds.) The Ryukyu Robins Isson depicts are highly biologically accurate. In works such as “Plants and Ryukyu Robin on Rock” (Private Collection) and “Ryukyu Robin in Cherry Blossom Forest” (Tanaka Isson Memorial Museum), you can see a male Ryukyu Robin surrounded by subtropical plants, stretching his chest, spreading his tail and lifting his head with its mouth agape. True to form, male Ryukyu Robins sing loudly in this posture in the dark forest. In being able to notice and depict such behaviors correctly, one can reason that Isson was a keen observer of the Ryukyu Robin. Perhaps he believed that the Ryukyu Robin’s most interesting act was their singing behavior.

Seitei also painted Ryukyu Robins. In this work, a male Ryukyu Robin rests facing upward on a snow-covered willow tree branch. While the details are realistic, the combination of a subtropical Ryukyu Robin in a snowy landscape is not. Moreover, while the act of hanging on a twig is common for birds that live on upper part of trees, such as Parus birds and Japanese White-eyes, it is unusual for Ryukyu Robins, which live in dark forest grounds. It may be that Seitei began the work by modelling the subject after a common small bird, then finalized the work by replacing it with a Ryukyu Robin. Despite how both, Seitei and Isson, depict the same Ryukyu Robin, their depictions are completely antithetical in their background, temperature, sound, and composition.

Considering their historical disparity, Seitei, who was from the Meiji period, cannot have known of Isson, who was from the Showa period. Yet, when placed in direct juxtaposition, it feels as if Isson’s realistic depiction predates Seitei’s fantastical rendition of the Ryukyu Robin. As two outstanding bird-and-flower painters, it seems inevitable that Tanaka Isson and Watanabe Seitei fated to be compared in perpetuity over time.

Author : Masao Takahashi Ph.D. (Ornithologist)

Dr. Masao Takahashi was born 1982 in Hachinohe (Aomori prefecture) and graduated from Rikkyo University’s Graduate School of Science. Dr. Takahashi specializes in behavioral ecology and the conservation of birds that inhabit farmlands and wet grasslands. Focusing on the relation between birds and art, he has participated in various museum and gallery talks.